Remember the 1990s? They were the years of Beanie Babies and Bart Simpson, designer yo-yos and the first color Game Boys, Doc Marten combat boots and everything plaid. From the Spice Girls to the Dixie Chicks, girl bands ruled. Michael Jackson thrilled us, and hip-hop turned pop on its ear (sometimes literally). Kiddies loved Disney epics like The Lion King, while adults flocked to blockbusters like Titanic. And late in the decade, a kid named Harry Potter enchanted “muggles” the world around.

In the everyday world, technology was creating its own kinds of magic. The Mosaic web browser brought the Internet to everyone, and Google was there to help us get around on it. Nokia offered the first mass-produced cell phone, text messaging launched a generation of future BFFs and BAEs, and MP3 players made music mini and mobile. The Hubble Space Telescope brought us a new perspective on the universe. And Adobe Photoshop ushered in the era when, if you couldn’t believe your eyes, you were probably right.

Meanwhile, in General Aviation

While pop culture and technology were flourishing, the early 1990s were a rocky time for general aviation. As an Airfacts Journal article noted: “The world economy was still climbing out of a recession. Manufacturers and pilots were spooked by the oil crisis. Airplane production plummeted to a trickle and product-liability lawsuits targeting manufacturers were pushing the price of new airplanes to unattainable levels for most recreational pilots.” Small plane production had dropped from around 17,000 per year in the late 1970s to less than 1,000 in 1994. The situation was dire enough that Congress passed the General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994 to limit the period of product liability on general aviation aircraft manufacturers.

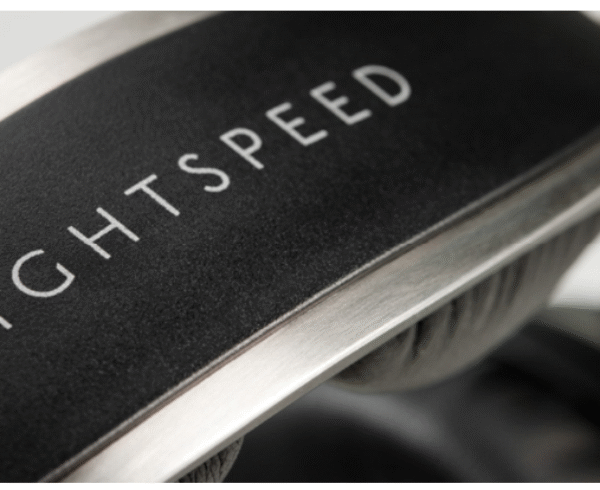

Enter Lightspeed

Into this inauspicious GA environment jumped Lightspeed Aviation. When we asked Allan Schrader, Lightspeed’s President and CEO, about the timing, he laughed and said, “You know, none of that is even a factor in my memory now. Maybe a prudent person with an MBA should have considered that. But one thing led to another.”

Allan had gotten into general aviation while helping a company that made intercom systems for aircraft expand into the passive headset market. When he became a partner in Lightspeed Technologies, he began to source and sell 1-way wireless microphones audio systems for singing and speaking and then classroom amplification. A supplier partner from his aviation days approached him and said, ‘Hey, you know how to design headsets and I have the capability to develop active noise reduction (ANR)!’” “ANR, as it turns out, is great for cancelling noise at low-end frequencies—exactly the kind of noise that pilots and flight crews have to deal with in small airplanes.

“What if we teamed up and make something better than the big boys?”, Allan thought. “I was naive enough to say ‘sure’, and that launched me on the journey of designing breakthrough ANR headsets that I’ve been on since 1994,” Allan explains.

Lightspeed’s K-series ANR headset was launched at EAA AirVenture 1996 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Allan says, “We had a little 10-foot booth in the south hangar, and people would come by, look at the banner saying we had an ANR headset for $400—at a time when no ANR headset was under $800—and they would say, ‘Who are you?’” Besides delivering ANR at a fraction of the going price, the K-series was the first aviation headset to use two AA batteries that lasted 30 hours. Other headsets at that time needed six batteries, which lasted only 10-12 hours. It was also the first to include a battery level indicator, and the first to use conformal foam ear seals for increased comfort.

Comfort, Quiet and Features

The first hurdle for Lightspeed was to get past the reaction “Lightspeed who?” (The company was often confused with Lightspeed Engineering that made fuel-injection systems for airplane engines.) Some good reviews in GA magazines helped. The next step was to get people to try the headsets. Allan’s team came up with an idea to prove to them just how good their products were. They bought an acoustic egg chair and replaced the speakers with a giant sub-woofer under the seat, then he recorded noise from 10 different airplanes to play through the speakers. Lightspeed would set up the egg in its tradeshow booth, playing the airplane noise inside the chair, and visitors could sit in it and compare the Lightspeed headset against a competitor’s headset. And then, Allan says, “We would sit back and ‘watch for the eyebrows,’” as the visitor realized that the Lightspeed headset really was as good at noise reduction as a competing $1,000 headset, and it was more comfortable.

Over the next decade, Lightspeed brought out the XL-series headsets, with different levels of noise reduction with an automatic shutoff feature to further extend battery life. Then the 3G series, the first aviation headset to offer an input for auxiliary devices such as cell phones and music players, intercom priority muting to ensure ATC took priority over the auxiliary inputs, and a treble/bass EQ setting.

The QFR (Quiet Flight Rules) series, introduced in 2000, offered the highest Noise Reduction Rating (NRR) of any passive noise reduction aviation headset on the market, and the Lightspeed Mach 1 in-the-ear headset, launched in 2005, offered advanced Lightspeed performance in a lightweight in-the-ear design.

During that season, Allan says Lightspeed’s reputation grew for both products and exceptional, personal customer support. “In the first decade of our products, we never charged anyone for repairs one of our headsets,” Allan said. “These pilots had trusted me to build a great product and I owed them much of my business success.” The company had transitioned from “Lightspeed who?” to offering “the best headset for the money.” In addition to value, Lightspeed became known for its comfort, quieting, and range of innovative features. “At one time, we were marketing 10 headsets (both active and passive) ranging in price from $119 to $650. We had a headset for everybody’s mission.”

All in all, it was a smooth ascent for a scrappy little company that launched in a changing market with goliath-like brand competitors. But Lightspeed was far from leveling off because waiting in the wings was Zulu. And that will be the next chapter of our story.

Nice story. My first Lightspeed headset was the original Zulu. I had planned on buying myself an ANR headset as a gift to myself for achieving my PPL the week before, then flying a rental 172 to AirVenture 2007. I tried all of the ANR headsets at the many booths, especially the highly coveted big “B”. However, I just couldn’t hear $1000 of noise reduction. At a booth with dozens of headsets hanging upon an arch that projected airplane noise under it, somebody handed me an unfamiliar silver headset. I tried it on, the airplane noise ensued, then the booth attendant pressed the button to activate the ANR. “WOW! I’ll buy one of those” I exclaimed. “You can’t.” I was told. There were only two demonstrator sets moving about AirVenture. I purchased an original Zulu to be shipped a later during fall, 2007. It’s been great. I still have it, and added a Zulu 2, upgraded to a Zulu 3. Please continue your history story.