In parts 2 and 3 of this series, we examined aircraft performance and mountain weather: what we have to work with vs. what we are up against. Part 4 of this series starts by developing some simple rules to operate by and then digresses into an important glider concept.

When approaching and crossing ridges, first notice the aircraft’s crab angle. This will tell you whether you are on the windward or leeward side of the ridge line. This, in turn, will tell you whether lifting or sinking air is more likely. Regardless, approach the ridge at a 45 degree angle (Sparky’s 1st rule – be in a position to turn toward lower terrain). You can commit to crossing the ridge if the aircraft’s throttle could be retarded to idle while still being able to glide to the ridge top (Sparky’s 2nd rule – never fly past the point of no return). A good rule of thumb is to plan to cross ridge lines with 2,000 feet of clearance for safety.

With regard to canyon flying, the biggest mistake a pilot can make is to fly straight down the center of the canyon. Flying the center may limit the aircraft’s turning radius in both directions so as to make a turnaround impossible without some extra maneuvering, assuming there is space to do so. If there is wind, it is probably best to choose the downwind side of the canyon. There are several reasons for this. Should a turnaround be necessary, the pilot has the whole canyon AND the turnaround is into the wind, shortening the aircraft’s turning radius. Furthermore, due to the aircraft’s crab angle, the turnaround is actually slightly (or significantly, depending on the wind strength) less than a full 180 degrees of heading change.

Sticking to these simple principles should keep the inexperienced mountain pilot out of trouble, but what if the worst happens? What actions do we take if we do manage to blunder into a 1,000 foot per minute downdraft? For this discussion, we will digress into a concept from the glider world called “speed-to-fly.”

What is “speed-to-fly”?

In his seminal work The Joy of Soaring, glider Carl Conway defines speed-to-fly as “the indicated airspeed that produces the flattest glide in any situation of convection.” For pilots, strong updrafts and downdrafts are realities of flying. But what’s the best course of action should you blunder into a strong downdraft? The natural temptation is to attempt to maintain altitude, but glider pilots, like Conway, are taught to react differently.

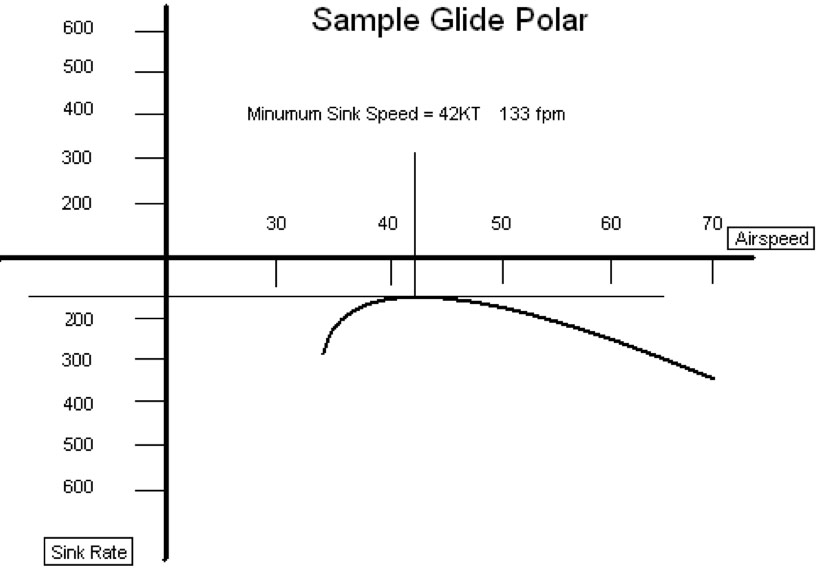

A glider POH contains something called a glide polar—see diagram below as an example. The polar is a simple plot of the glider’s sink rate vs. airspeed; it shows the glider’s L/D performance at various speeds. Immediately obvious is the glider’s “minimum sink” speed—the speed at which it loses minimal altitude per unit time. Minimum sink speed is the appropriate speed-to-fly in a parcel of lifting air—it will optimize the glider’s climb.

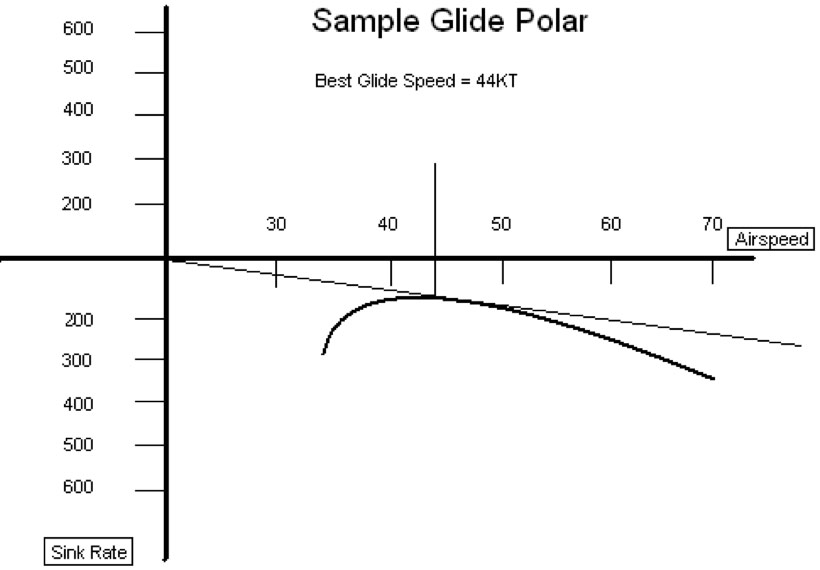

A line drawn from the origin represents a particular L/D, and the one tangent to the polar (see the figure below) represents the glider’s max L/D. The corresponding speed is the glider’s best glide speed absent any atmospheric convection.

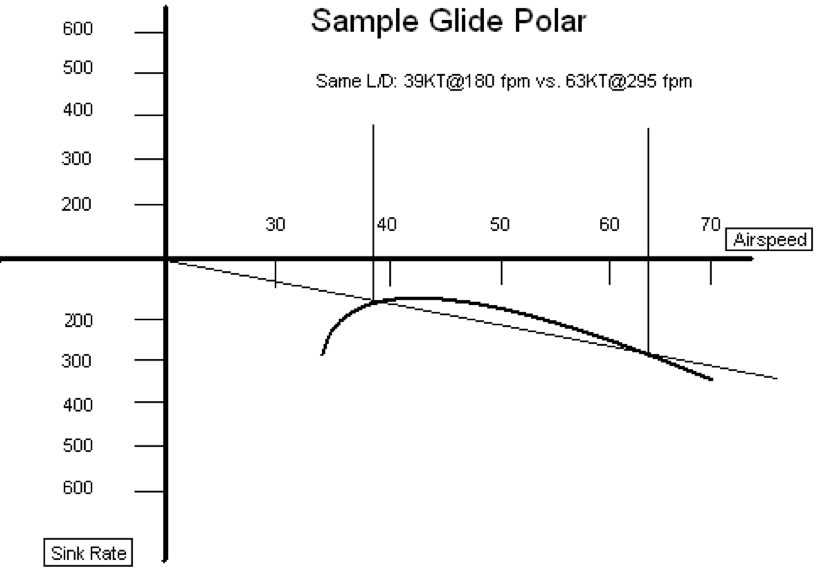

Notice in the figure below that there are two speeds which yield any L/D less than max L/D, one lower and one higher than best glide speed. The salient fact is that the slower speed differs from best glide speed by only 12%, while the faster speed differs from best glide by a whopping 43%. In other words, the penalty for flying too fast is not as severe as the penalty for flying too slow. This is typical of most glide polars.

That sinking-air feeling

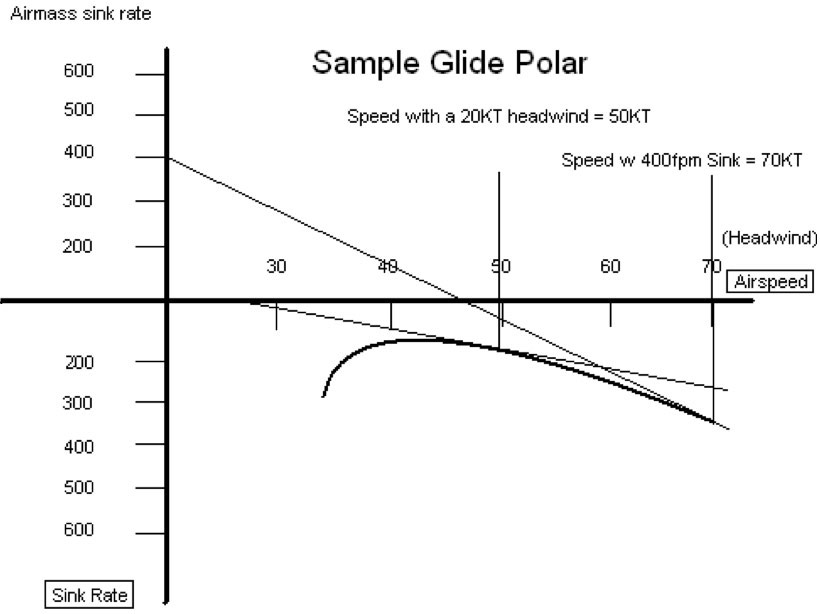

If the glider is flying in a parcel of sinking air, the tangent line’s origin can be adjusted in order to find the correct speed-to-fly. If the parcel is sinking at 400 feet per minute, we would have to adjust the entire polar downward by 400 feet per minute. Instead of moving the whole polar, the tangent line’s starting point can be adjusted, as in the figure below; note that, in this case, the tangent line contacts the polar in a different spot, and therefore implies a different speed-to-fly. The adjustment is similar in the presence of a headwind. In both cases, the recommended speed-to-fly is higher than with no convection or wind.

Gliding through the math

Let’s look at another abstract instructional light-airplane example: say a light aircraft with a best climb speed of 80 KIAS and a maneuvering speed of 120 KIAS is flying into a 20-knot headwind and encounters a 1,400 foot per minute downdraft. This situation smacks of a ridge or wave encounter, and 1,400 feet per minute is the vertical component of a 20-knot wind deflected downward at a 45-degree angle. Let’s further assume that the aircraft is capable of climbing at 400 feet per minute (a high-density altitude), and that the downdraft is a half-mile wide. If the aircraft maintains best climb speed during the encounter, it experiences a 1,000-foot per minute sink rate for 30 seconds—a net loss of 500 feet. If it maintains maneuvering speed, it experiences a 1,400 foot per minute sink rate for only 18 seconds: a net loss of only 420 feet.

Yes, the examples I give are abstract, but they’ll make pilots of light aircraft nod their heads in recognition. When it comes to speed-to-fly, perhaps the glider folks are onto something.

Leave a Comment