As pilots, we are trained to overcome adversity in the cockpit. From weather issues to electrical, mechanical, and even total engine failures, we are taught to never stop flying the aircraft. However, for an unfortunate few pilots each year, their best efforts in the cockpit result in an off field landing over remote or inhospitable terrain. Once on the ground, the most pressing issue becomes a swift rescue.

Since the FAA mandate in 1973, the defacto standard for aircraft rescue has been the Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT). The original ELTs transmitted on 121.5 MHz (guard frequency) and the position of the downed aircraft had to be triangulated using directional receivers employed by rescue agencies such as the Civil Air Patrol. More recently, modern ELTs using 406 MHz are capable of transmitting the aircraft’s precise GPS position, but only if this option is configured during installation. Unfortunately, ELTs have never been a reliable method of finding an aircraft following a crash. Aside from an overwhelming number of false alerts, the units themselves have a questionable track record in real-world accidents.

A 2017 NASA study of ELT effectiveness found that out of 86 “Injurious or Fatal Accidents” over a five-year period from 2009-2014, the ELT failed to operate in 61 of them. That represents a less than 30% success rate for ELTs when they were needed most. The reasons were varied, but included antennas or cables failing, as well as testing that showed that the antennas would remain capable of transmitting a signal less than one minute if exposed to fire. Although ELTs remain a legal requirement, the facts seem to indicate that they are not your best bet as a lifeline to get help.

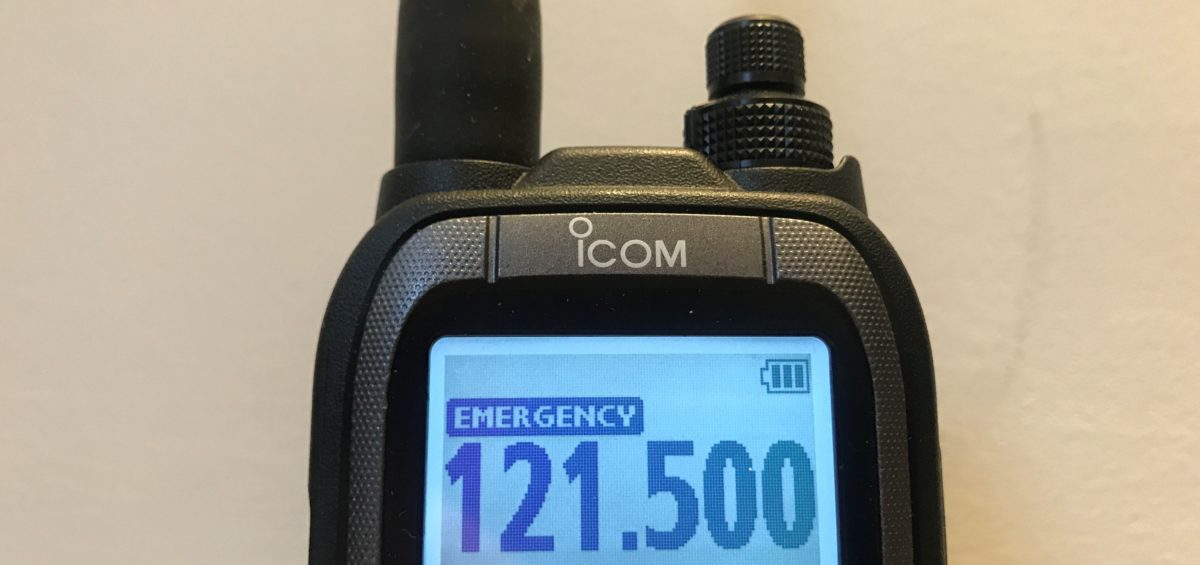

The next historic “go-to” for rescue is the portable VHF radio. The advent of low-cost, handheld aviation radios has made them a mainstay for nearly every pilot’s flight bag. Their “triple-duty” role as a backup for in-flight communications, emergency rescue communications and airport/airshow entertainment receiver makes them an easy sell. However, in reality, they aren’t an ideal tool to reach out for rescue. VHF radios require line-of-sight to communicate and there is the additional requirement that both transmitter (you) and receiver (your rescuer) be using the same frequency. You could certainly use 121.5 to call for help, but not every aircraft likely to fly overhead may be listening on the frequency. A better approach might be to set the radio to scan mode and wait to hear an aircraft transmitting nearby on a different frequency…then call for help on that. It’s better than relying on your ELT, but the odds aren’t in your favor. Oh, and don’t forget to keep that radio charged. The last time I pulled my radio out of my flight bag it was dead…so, lesson learned: “Charge Before Flight ”.

Jumping WAY up on the technology ladder, we come to Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) and GPS trackers. These small, portable units utilize GPS satellite technology coming down from the heavens to track your position and then reach back up again to communications satellites to send your position out to whomever you setup to track you. PLBs such as the SPOT Satellite Personal Tracker and Garmin inReach Satellite Communicator are constantly tracking your GPS position, but only report it out when activated (unless put into a tracking mode). GPS trackers such as Spidertracks default to sending your location at regular intervals so that friends or family can watch your progress on a flight or hike through the wilderness. The challenge with both systems is that they don’t directly indicate that you need rescue until you activate them in an SOS mode. This means you need to be conscious and able to reach/activate the units to call for help. That is unless you link your GPS tracker to your flight plan with Flight Service. Leidos’ Flight Service website (1800wxbrief.com) allows you to register and link GPS trackers such as Spidertracks and InReach with every flight plan that you file. Their system automatically monitors the tracking reports along with your flight and alerts Flight Service if you appear to stop moving during your flight. It’s an excellent way to have someone watching your back, even when you are outside of radar coverage.

A note about subscriptions: In general, PLBs do not require any subscriptions as they are intended for emergency use only and send out a signal on government-run satellite systems for the sole purpose of rescue operations. Messenger devices (GPS trackers) or enhanced PLBs with messenger/tracking services are generally run by private companies and require subscription services. For example, at the time of this writing SPOT charges a $19.95 activation fee for their devices and subscription fees range from $9.95/month to $29.95/mo. The Garmin In-Reach monthly fees vary from $11.95/mo. to $64.95/mo. and Spidertracks plans range from $29/mo. to $79/mo. The premium you pay for these tracking services is representative of their use for much more than search and rescue. They are a means for you to stay in touch with loved ones, allow them to track your progress and remain connected when you’re out of traditional cell coverage.

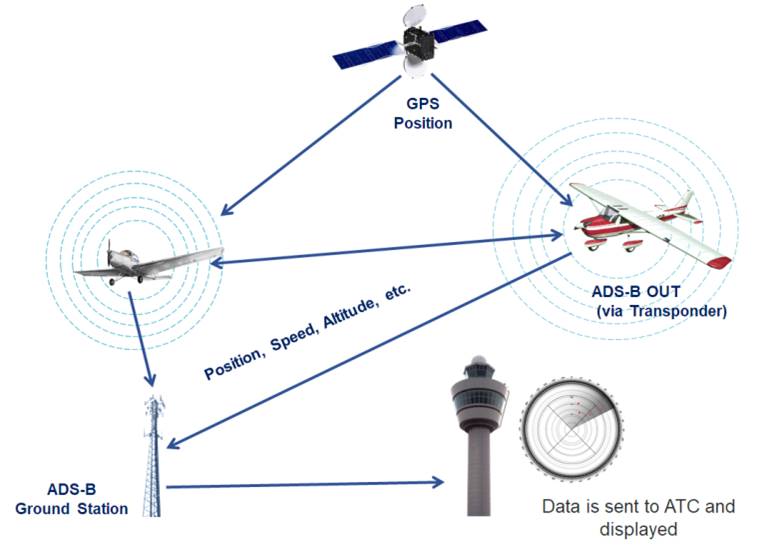

If there was one good thing that the dawn of 2020 brought to aviation, it was the passing of the ADS-B mandate deadline. We now live in a world where nearly all aircraft have been equipped with ADS-B, sending out a constant stream of GPS-based position reports that can be used by rescuers to track the progress of a flight up to the point that contact was lost.

As a ground-based system (in the U.S.), ADS-B has coverage limitations based on altitude, terrain, and ground-station coverage. Therefore, it can still be a dead-end if an aircraft is lost in remote terrain. However, it’s far more accurate and has better coverage than traditional transponder & radar tracking ever had. It should be noted that Canada is implementing a satellite-based ADS-B system that will allow complete coverage, regardless of the terrain. That’s good news for the safety of Canadian pilots who fly in remote areas, bad news for non-Canadian pilots who spent thousands of dollars to equip their aircraft with ground-based ADS-B systems and want to fly in Canada. Those folks will have to upgrade to ADS-B systems with “Diversity”, which is a fancy word for systems that have an antenna on both the top and bottom of the aircraft.

The last and arguably highest technology option is one we all have handy: your cell phone. The reality is that most modern day search and rescue operations begin and end with cell phone tracking. Most rescue agencies have emergency access to your phone’s location as reported to the cell phone network. Even while flying, if your phone is turned on, you are bouncing in an out of different networks and towers. In addition, while within range of data networks such as 3G or LTE, chances are that your exact GPS location is also being reported out in a way that rescuers can track. Of course, cell phone tracking can only do so much if you’re flying across vast regions without coverage. But, your flight path and speed can still be extrapolated from the last reported location to help rescuers locate you even if your travels take you out of coverage.

The bottom line is that the technology options that are right for you depend on the type of flying you do. Pilots flying in the sparsely populated backcountry have a greater need of independent solutions than those flying between major cities in crowded regions. For those pilots, installing a 406 ELT in conjunction with GPS position reporting is essential. In addition, PLBs add an extra level of security that’s critical in the backcountry. For pilots who rarely leave populated areas, leaving your cell phone on may be good enough. However, no piece of equipment is as important as having someone know where you are and where you are going at all times. This includes putting ATC at the top of the list. Their job is literally to watch your back. Use flight following anytime that you’re within radar coverage, even if you’re just out maneuvering. There’s nothing wrong with telling ATC that you’ll be “maneuvering at XXX location” while you’re out shaking off the rust and just having fun. They’ll be able to vector traffic around you and keep an eye on you as well in case you drop off the scope without warning.

For those pilots who routinely fly out of radar coverage, file a flight plan and fly the plan. And, choose the technology solution that’s right for you so that you can call for help if needed. In the event of an off-airport landing, early rescue is critical to the survival of both you and your passengers. There are many options available for a surprisingly low cost, and the peace of mind is priceless.

Leave a Comment